Our friend John Wheatcroft, journalist and novelist, has written a piece about J.L. Carr, based on his meeting the author and publisher in the 1990s and later his son Bob Carr in 2007. Here we reproduce his article and tip our hats to the Carrs and the Quince Tree Press: purveyors of fine books, pamphlets and county maps…

Bob Carr is both touched and surprised by the affection in which his novelist father is still held.But he nearly fell over when he learned that his dad, J L Carr, had once prepared a three-course meal for a complete stranger.

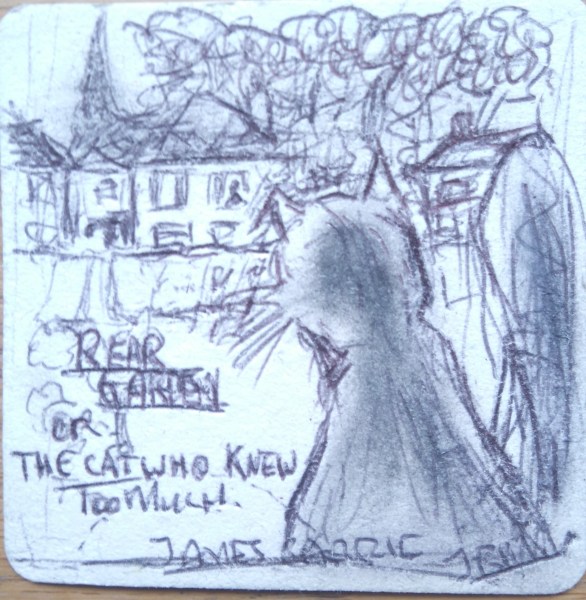

Carr junior came up from Suffolk in 2007 to visit South Milford in North Yorkshire, where his father had once taught in the local primary school. Villagers were holding a week-long celebration of J L (Jim) Carr’s life, culminating in the opening of a ‘Reflective Garden’, complete with a sculpture dedicated to the writer. My anecdote was one of many Bob listened to patiently during the evening, and it was evidently the most unexpected.

James Lloyd Carr died in 1994. The year before, I had been visiting a friend in Northamptonshire when I realised that I was close to his home. I phoned and asked if I could meet him. Carr, though baffled as to why I should wish to do so, agreed and suggested lunch the following day at his house in a suburb of Kettering.

I arrived with a bottle of New Zealand sauvignon, which was placed gingerly in a cupboard. Ten years later, when reading Byron Rogers’ brilliant biography, The Last Englishman, I learned that Carr, not a great drinker, once handled a gift of a bottle of whisky as if it might explode. The hearty three-course meal that he provided for me – soup, steak and kidney pie and jam roly-poly – wouldn’t have been out of place in a 1950s’ Lyons’ restaurant.

His twin obsessions were writing – he was full of praise for Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch which he had reviewed for a national newspaper – and anything to do with Yorkshire. When I told him that my sister lived in Womersley, a village near Pontefract, he rushed off to find an atlas.

He asked me if I did much writing and seemed desperate to deter me from pursuing it. Many young writers, he said, are too eager to get into print and need to experience more of life first.

I was almost 40 at the time but, I suppose, a spring chicken in the eyes of a man whose first book was nominated for the Booker Prize several decades after he started work on it. Carr made the Booker shortlist (for the second time) in 1985, with The Battle of Pollocks Crossing, when he was 73.

A few things had happened in the intervening years, of course. Carr worked as a teacher, latterly as a primary school head, until 1967. He then set up as a publisher in his spare bedroom, drawing and selling maps of the English counties. He also produced little dictionaries and tiny volumes (many are still available) about the great poets. His eccentric Dictionary of Extra-Ordinary English Cricketers (1977), which was republished in an expanded, hardback form by Aurum Press in 2005, was a great success. It omits Sir Donald Bradman but includes Max Beerbohm who subscribed a shilling to W G Grace’s

funeral ‘not in support of cricket but as an earnest protest against golf’.

Carr also had several novels published (all after he passed 50) to critical acclaim but modest sales.

He said: “The book that became Pollocks Crossing was deservedly turned down many, many times under different titles. Finally I put it away until I’d published five other novels. Then I wrote it again in cold blood.”

That phrase came up again and again. Carr saw writing as a craft; the novelist had to take account of what publisher and public want.

The word that springs to mind to describe his novels is idiosyncratic. They’re old- fashioned, in the sense that the virtues of character and narrative are important, but quite different from one another: How Steeple Sinderby Wanderers Won the FA Cup (not sponsored by Budweiser of the Emirates) is a comic account of a village football team’s progress to Wembley. A Month in the Country, also shortlisted for the Booker, is a nostalgic idyll set in a gloriously hot summer after World War One. That was the moment, he reckons, when his commercial instinct served him best.

He said: “Most people like reading about the past, life seemed more leisurely before the motor car age. They like a love story without too much sex – in any case people of my generation are very reticent about sex. And people like hot weather. If incorporating those elements is not a cold-blooded approach, I don’t know what is.”

Carr’s love of design work and his commercial ‘nous’ came in handy when he was offered what he described as ‘a disappointing advance fee’ for his 1988 novel, What Hetty Did. He decided to go it alone, publishing through his own Quince Tree Press ‘a superior looking book’. After three editions and 8,000 sales he had made a handsome profit, encouraging him to buy back the licences for most of his other works and to publish them himself.

He told me that he expected A Month in the Country to survive (“after all, it’s an examination book now, people are having to read it”) but felt that otherwise his desire to please counted against him.

“I’m rather a specialist taste. If you really want to make a big reputation as a writer you need to keep on working in the same genre. If you chop and change, as I’ve done, you’ll lose readers as well as gain them.”

Perhaps posterity will prove Carr to be wrong. In The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, Evelyn Waugh offers a summary of his protagonist’s literary credentials. Pinfold’s writing, he says, might be seen in 100 years’ time as typical of a generation of novelists ‘notable for elegance and variety of contrivance’.

That could well serve as a summary of Carr’s literary output. In a couple of generations’ time, when we’ve tired of some of the more meretricious contemporary heavyweights, Carr might just be still with us.

Meanwhile, Bob Carr keeps the flag flying, continuing to sell his dad’s books under the Quince Tree Press imprint (www.quincetreepress.co.uk) and to marvel at his popularity and previously unearthed talents in the kitchen.

John Wheatcroft’s novel Here in the Cull Valley, published by Stairwell Books, is available online….